The Radio Squirrels of Point Reyes

Tucked away on remote area of National Park land, a small, but dedicated band radio enthusiasts are operating the last morse-code station in America.

Roy Henrichs is double booked. From a remote commercial radio station in Northern California, he sends the only maritime morse code signal from North America out onto the airwaves. He is one of the only commercial operators certified to send the signal. He is also one of the few operators able to receive the signal in the area. It means that the only WW2 era ship in the area, the SS Jeremiah O’Brien, has no one to tune into a historic frequency meant specifically for it. “To put it very simply, I can only be in one place or the other,” says Henrichs.

If morse code and maritime telegrams seem outdated, they are. KPH, a ship to shore maritime commercial radio station that Henrichs helps keep afloat, closed years ago. The only thing keeping the historic KPH station on the airwaves is The Maritime Radio Historical Society, a small but dedicated band of radio technicians and operators. Without this self-proclaimed group of ‘radio squirrels’ the transmitter and receiver sites at Point Reyes National Park would’ve quietly faded into memory.

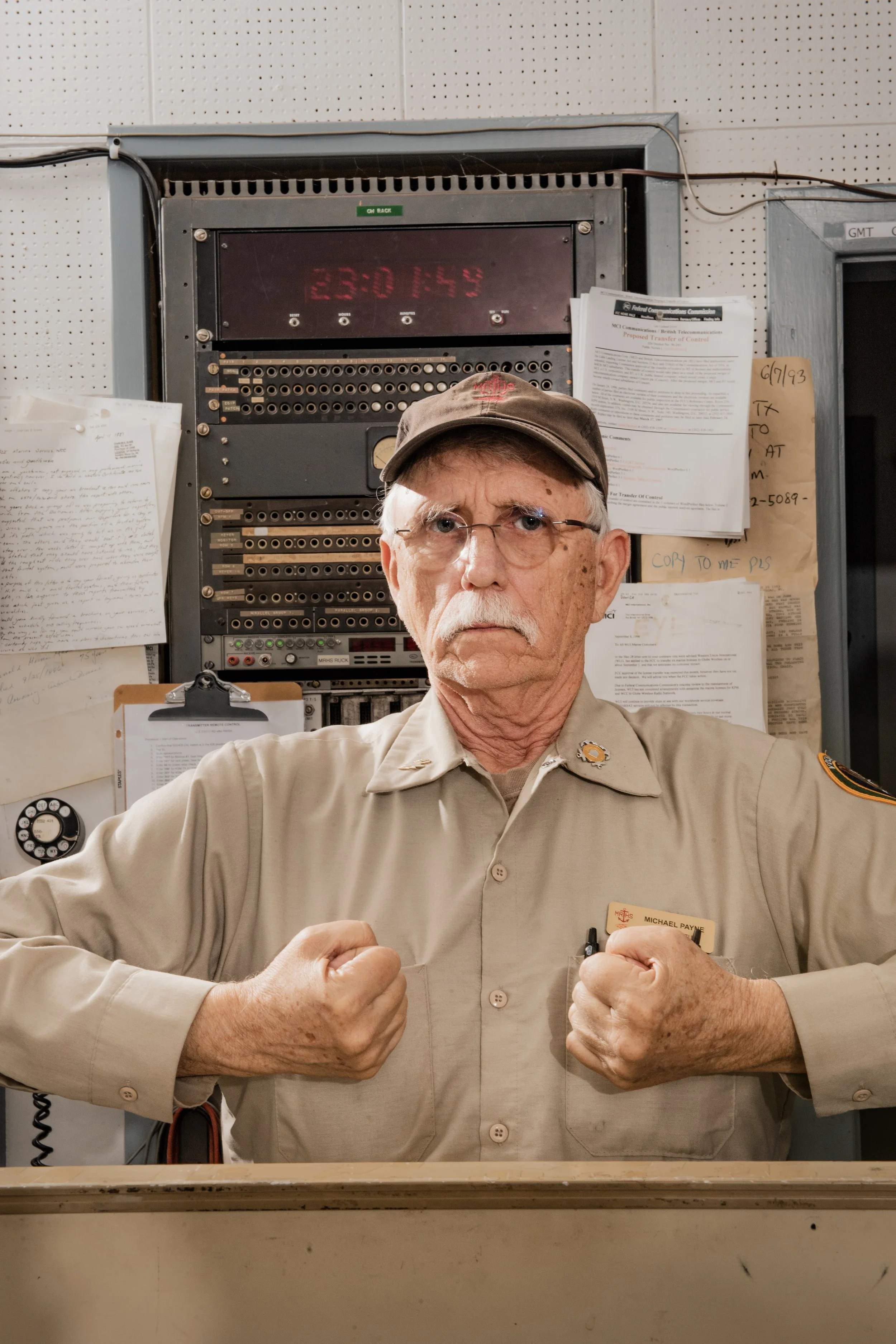

Every Saturday, the radio squirrels gather at one of the two radio sites near Bolinas, California for “services of the continuous wave” where the sacraments are coffee and pastries. After stories are swapped and coffee consumed, part of the group stays at the transmitter site to send press and weather reports and the rest head 26 miles north to maintain and operate the receiving site.

Despite the weekly devotion of the radio squirrels, the transmitter and receiving sites are a shadow of their former glory. In the early 1900’s the station was a commercial ship to shore communications hub from the Pacific Coast to the world. The station was one of the first to receive news of the attack on Pearl Harbor. As telegrams and morse code fell out of use, the KPH was taken off the airwaves in 1997 and both sites sat abandoned. But they weren’t forgotten. Maritime Radio Historical Society Founders Tom Horsfall and Richard Dillman visited both sites when they were in full operation. Two years after the sites closed, Dillman and Horsfall convinced a security guard to let them have a look inside. What they found was radio machinery still online, an unexpected time capsule with the airwaves still crackling. “Even yet I still get goosebumps when I think of it. We walk in there and it looks like they left 20 minutes ago because the Morse code keys are still on the tables… The last thing they did was make sure that the receivers were still on. They're maintaining a symbolic watch over the airwaves. We thought that was just tremendously moving,” says Dillman. Horsfall and Dillman knew they had to bring the whole system back online, so they set about convincing the National Park Service to allow them to get a team of volunteer radio technicians into the site to get the KPH radio signal up and running again.

Even though the station was brought back from the brink of extinction, its future still looks uncertain. The radio squirrels are older, the receiving and transmitting sites are remote, and it’s an undertaking to keep a living museum like KPH running. As Henrichs knows, there are only a handful of technicians able to a commercial maritime radio site and there are only so many radio squirrels like him and his cohort. There are still glimmers of hope. Henrichs has a new department member at the SS Jeremiah O’Brien working on a license to operate and receive morse code messages from KPH. And at a commemorative radio event at the station 17-year-old Luis Membrila Martinez made the trek to KPH with his mother to learn more about morse code and find community with fellow radio squirrels who still revere the power of the airwaves. “Just with tapping your fingers you're outputting so much power into those antennas. I just think that's incredible,” says Martinez.